As the rest of health has transitioned towards some form of value-based or quality-contingent payment (whether through the Readmissions Reduction Program, Hospital Value-Based Purchasing, Physician Quality Reporting System or Meaningful Use), post-acute care has anxiously waited on the sidelines. No longer. With the passage of the IMPACT Act, the extensive growth of ACOs and Bundled Payment for Care Improvement pilots, and growing sophistication of quality measures and data analytics, post-acute care providers are finding themselves increasingly in the spotlight to prove they can offer higher value outcomes over alternative providers or lower-cost settings.

For the past few years, both healthcare networks and consumers have relied heavily on the CMS Five Star Rating, which, as I and others have written about before, is an imperfect guide to quality. For hospital-led systems, rehospitalization measures are increasingly becoming an important marker of quality. In a recent Mcknight’s article, Steven Littlehale of Pointright describes the challenge of narrow networks based on just a few measures. Instead, he proposes using “smart networks” based on several outcome and process measures. Careport Health, a start-up based in Boston, is attempting to do just that.

With the impending transformation towards value-based payment models and smart referral and partner networks, along with growing sophistication on outcomes and measures, how can post-acute care providers remain competitive? Here are three areas to consider:

1. Build a high-reliability, outcome-based organization.

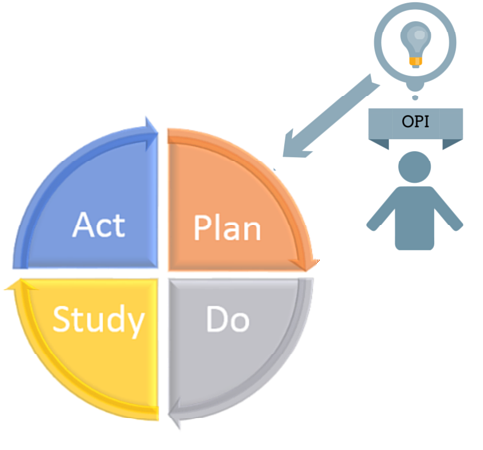

The days of focusing on RUG rates and pushing length of stay as high as possible are over. The five star rating system, while still important, will no longer be the key to acceptance by partner networks. Providers instead need to develop strong, consistent systems to provide high-quality care as effectively and efficiently as possible. Not only does this require a competent therapy team, but providers must also have engaged staff, from CNAs to housekeeping aides, who all contribute to the well being and satisfaction of guests. The need for resiliency means providers must adopt a holistic view of their operations, rather than relying on a few heroes to steer the ship. Information will need to flow continuously and seamlessly through the organization, enabled by technology but driven (and utilized) by capable employees. A culture of continuous improvement and rigorous root cause analysis is essential, which requires deep organizational investment in learning, problem solving, and engagement.

Investments in culture and institutional capacity will have a rollover effect as well: post-acute care providers who position themselves as meaningful, exciting and challenging places to work will help stem the tide of turnover that has long plagued the sector, and provide a buffer against the growing shortage of direct care workers.

2. Invest in long-term relationship management.

Providers can no longer forget about guests after a discharge is complete– nor should they wait until admission before forming relationships. Instead, providers need to become sources of information about aging and care options for the entire community. They should also invest in interactive care coordination and follow-up technologies to ensure emergent needs and care challenges can be addressed before they become more costly. From call center-based coordination to remote monitoring technologies, the options are quickly growing.

This change to long-term relationship management is both a new challenge—and new opportunity—for providers. Utilizing their existing social services, recreation and transportation infrastructure, skilled nursing providers can quickly and effectively provide low cost, high value assistance to keep elders in their homes after discharge from a skilled facility.

Providers can also take the lead on facilitating care coordination between a guest’s primary care team and other needed resources, such as social services and supports offered through Area Agencies on Aging. Engaging elders in the community also provides natural referral networks for long-term or community-based care services the organization also provides.

3. Expand service lines to target newly available revenue streams.

Many senior housing providers have long stayed away from Medicare services because of the onerous regulations and increased complexity. Bundled payment and ACO models provide innovative opportunities to partner with or build home health agencies and provide high quality, inclusive rehab services in lower-cost-of-care settings. For senior housing providers, this can open up lucrative revenue streams while also providing needed resources to build clinical care capacity and resident offerings. By contracting directly with innovative ACO programs, providers can also avoid the hassle and uncertainty of Medicare billing, as well.

For hospitals and health networks, partnering with senior housing communities provides an ideal way to support a targeted, high risk population with minimal investment of resources. Using analytics and care coordination services like Care at Hand, Life2 and Caremerge, providers can seamlessly integrate expanded services into existing workflows and structures. Non traditional senior housing providers, such as HUD 202 buildings, can also tap into these new opportunities to expand revenue while reducing overall healthcare costs. For instance, housing organizations are partnering with ACOs to reduce hospitalizations– and capturing a piece of the savings. Senior housing providers are providing home care and meal delivery services to local neighbors– making money and building brand awareness. Assisted living communities are participating in bundled payment initiatives to manage chronic conditions in the community in exchange for health IT investments and care management support.

Change is quickly coming to the post-acute care space. This includes not only traditional providers, like skilled nursing facilities, but also assisted living and senior housing communities, home health and home care agencies, and ancillary service providers. Organizations should position themselves now to be an integral value-based partner with these new opportunities or risk being left with outdated service offerings— and empty buildings.

You can learn more about how eSSee Consulting helps providers and Health IT companies capture these new opportunities by visiting our Solutions.