In 1943, Edwin Land, while on vacation with his family, took some photographs of his daughter, Jennifer. Like any good three-year-old, Jennifer wanted to see the results of the picture right away. “Why can’t I?,” Jennifer asked. This simple yet powerful question led Land and his company, Polaroid, to develop products that transformed the experience of photography.

Why, What If, and How

In Warren Berger‘s new book, A More Beautiful Question, Land’s story is one of many used to illustrate the importance of not only questioning (itself a lost art among adults and organizations) but in also asking the right questions (primarily why, what if, and how) as a catalyst to innovation. The power of questioning is already revolutionizing fields from marketing to technology startups, and although Berger’s book has barely been out a month, I suspect it will become one of the top business books of the year.

A More Beautiful Question is particularly timely for aging services, as a confluence of forces– from payment models to demographic needs to disruptive technologies– are bringing fundamental changes quickly into focus and now, more than ever, organizations need to deeply question the core tenants of their organization as a precursor for survival.

The why, what if and how questions form the triad of powerful, leading devices for questioning. For why questions, Berger recommends the following process:

- Step back.

- Notice what others miss.

- Challenge assumptions.

- Gain a deeper understanding of the situation at hand, through contextual inquiry.

- Question the questions we’re asking.

- Take ownership of a particular question.

Many providers today are struggling with declining reimbursement, razor thin operating margins, maintaining quality of care, and meeting the needs and wants of a quickly changing population. Why questions can be incredibly useful in asking, “Why are we providing this service line?”, “Why aren’t we meeting these needs?” and even “Why are we here?”

If why has “penetrative power,” Berger writes, “what if [has] a more expansive effect– allowing us to think without limits or constraints, firing the imagination.” Several organizations have used the what if question to create groundbreaking innovations in aging services already: “What if we stopped building bricks and mortar?” (The CCAH model), “What if we made senior centers as appealing as Starbucks?” (MatherLifeways Cafe Plus), and “What if we combined predictive analytics with remote monitoring? (HealthSense, HealthSignals, CarePredict, and several others).

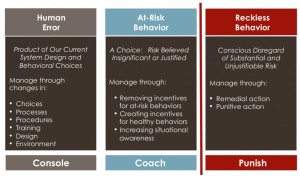

The final crucial question, how, is where results are created. Berger points to a number of examples that highlight the value of fast prototyping (Eric Reis and the Lean Startup) and test and learn (referencing Bloomberg’s pilot programs in NYC). Both of these strategies can be incredibly useful to aging services providers, who oftentimes think an idea to death before even launching a trial. For organizations that are able to test out new ideas and programming, it’s important to measure results carefully. Ask the question “Am I failing differently each time?”, Berger writes, drawing on IDEO founder David Kelley’s observations on the subject. This is particularly useful in responding to adverse events, as the lack of learning inevitable leads to policy creep: the tendency to respond to any event by writing a new policy or creating a new form.

Learning Organizations

I’ve heard many providers refer to themselves as “learning organizations,” popularized by Peter Senge, et al., in the book, The Fifth Dsicipline. The reality, however, is that very few actually embark on the journey to implement the disciplines necessary– systems thinking, personal mastery, mental models, shared vision, and team learning– mainly because they aren’t adept at questioning correctly.

One of the biggest reasons I love lean thinking is the emphasis on constant reflection and continuous improvement. Aging services providers, always already trying to do too much good work with too few resources and supports, tend to aggressively justify their current operations, values and faults rather than deeply question their core work. “We’re doing the best we can for our staff,” rather than, “How can we pay our staff a living wage?” “You have to move to assisted living to get services,” instead of “What if we built up services in place by leveraging other offerings?” This is unfortunate, foremost for its detrimental impact on persons served– and will likely be lethal over the coming years to organizations that can’t make the shift. (Polaroid, itself, is a great example of why learning must be constant, going bankrupt in 2001 after underestimating the impact of digital cameras.)

Questioning

Peter Drucker, considered to be the father of management, famously consulted with organizations not by providing answers but by asking crucial, if sometimes rather obvious, questions. The power of questioning, as Berger lays out so clearly in his book, will indeed be one of the biggest differentiators in the field of aging services moving forward. There is great future need, for sure, but it will no longer be met by senior housing alone. The current explosion into remote monitoring, home and community-based services, and intergenerational communities is only the tip, and providers need to start now to build strong organizations suited for deep questioning.