Change is difficult for most people. It usually feels easier and less risky to keep the status quo. People settle into certain procedures and relationships to accomplish work, and, over time, these patterns become expectations and rules for all to follow.

When making changes in organizations, it’s important to manage both socio-technical change– the changes of people and work processes– and emotional change– the change process itself as experienced by the people involved. If you are implementing a new dining program, the socio-technical changes would be the menu changes, the different roles of staff, new food items needed, etc. The emotional changes would involve how CNAs feel about serving in the dining, how department managers feel about increased responsibilities, how the foodservice director feels about less oversight over the food program, etc.

Change Management in 8 Steps

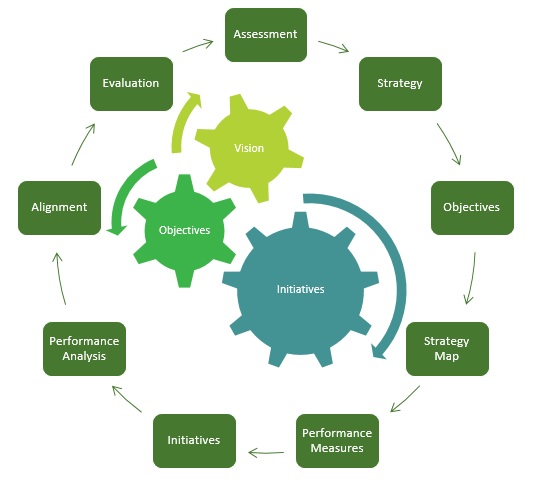

John Kotter, a well-known leadership professor from Harvard Business School, has studied change initiatives extensively. Specifically, he has looked at why some change efforts succeed while many other change efforts fail. (Kotter estimates that 75% of large organizational change initiatives fail.) Based on his extensive research, Kotter has developed an eight-step model for improving change processes. (Kotter, Leading Change, 2012) The steps are:

1. Increase the sense of urgency: People need to understand why they must change. Whether it’s a new payment model or different resident expectations, it’s important to make the case for change. A common example is to imagine you are on a burning off-shore platform. While jumping into the ocean seems terrifying, it is the only way forward with a chance at survival.

2. Build the right team: Once again, the team is crucial to success with changes. Make sure you work hard at building a strong, committed team. In the old days, it may have been important to have staff that followed instructions and didn’t rock the boat. Now, however, we need people who can problem solve independently and aren’t afraid to speak up when they notice a way to better serve residents.

3. Get the right vision: Know where you are trying to go. For most organizations, focusing on the needs of the person served is at the core of their mission, and it’s usually fairly easy to align the vision with this mission.

4. Communicate for buy-in: Communicate, communicate, and communicate. Use a variety of methods and materials, be frequently present, and engage staff to ensure understanding. Rarely has a change initiative in any organization been over-communicated. Remember that communication is a two-way street, too: don’t just shovel out memos and information—listen to feedback and make sure to engage all in the process.

5. Empower action: Leaders cannot do everything themselves. Instead, work hard to empower staff to make decisions, and support them, even if the decisions turn out to be wrong. Mistakes are usually the best way to learn how to do better, so take those opportunities to mentor staff rather than punishing them.

6. Create short-term wins: Don’t begin with a giant, long-term overhaul, as people will tend to lose interest and commitment to progress. Focus on small, visible goals first to build excitement and engagement. One of the reasons why 5S is a great starting place is that it’s both easy and plain to see. People see and experience the change and are much more likely to work on larger projects.

7. Don’t let up: Once a change begins, understand there will be peaks and valleys. Don’t give up on the goals and vision. Push forward with focus and dedication to the team.

8. Make it stick: For change to be successful long-term, it has to become part of the culture. This is as true for Lean and improvement as anything else. Build improvement thinking into every part of the culture, from orientation to evaluations to celebrations. Ensure that respect for people is practiced by everyone in the organization and that everyone spends time thoughtfully reflecting on how to do better. (Kotter, Getting Change to Stick, 2011)

Emotional Transitions

William Bridges, in Managing Transitions, developed a model for managing the emotional impact of transitions (Bridges, 2009, pp. 4-5):

1. Letting go, losing, endings:

When implementing change, it’s important to recognize the loss associated with letting go of old ways. Oftentimes, the people who struggle the most with this will be the best employees—after all, they have been the most successful in the old system. Spend time preparing for the transition by talking about the reasons for the change and how it will benefit residents. Build up the need for improvement. Also, understand that people are generally more likely to take a risk to minimize a loss (holding on to the status quo, for instance) than to take a risk to obtain a gain (a better process or outcome). That’s why even a positive change can be hard for people to accept.

2. The neutral zone:

The neutral zone describes the uncertain area between the old and new. Things are different, but not quite settled. Staff experience confusion and uncertainty in what’s happening and where the organization is going. Communicating a strong vision, encouraging people to try even if mistakes occur, and finding short-term goals to mark success are all crucial waypoints to guide the team through the neutral zone.

3. New beginnings:

New beginnings can be exciting, but there is often a tendency to slide back. To fight this tendency, active engagement from leaders is a must! You must work hard to build the new way of working into the very culture of the work area, from training new staff to ensuring that resources and rewards are aligned with the new way.

Moving Forward

The need to change is neither going away nor slowing down. But applying a good change management framework, along with proven tools and techniques, can help ‘grease the wheels’ that will lead to better adoption, less frustration and better outcomes for residents.

The need to change is neither going away nor slowing down. But applying a good change management framework, along with proven tools and techniques, can help ‘grease the wheels’ that will lead to better adoption, less frustration and better outcomes for residents.

Embarking on a change initiative in your organization? Feel like you are stuck in the mud? Get in touch and learn how we’ve helped organizations just like yours move ahead of the pack.