The manager has an open office policy. He involves staff in decision making, asks for feedback about new programs and initiatives, and helps out on the floor often. Still, he frequently finds staff are hesitant to speak openly about problems they see and challenges they face in their everyday work. He oftentimes doesn’t find out about issues until they become big problems, and there is a steady stream of bickering among many of the staff members.

The manager has held meetings to talk with staff about his desire for everyone to communicate openly and proactively. He assures staff they can drop by his office anytime—he almost always arrives early and leaves late. He walks the halls to check in with staff and asks how he can help. Still, the fundamental challenges remain. So what is missing? Why are his staff still reluctant to engage?

A key ingredient to high functioning teams is “psychological safety,” a term that describes individuals’ perceptions about the risks of their actions on interpersonal relationships. Amy Edmundson, a professor at Harvard Business School, has researched psychological safety and its impact on team performance extensively: “It consists of taken-for-granted beliefs about how others will respond when one puts oneself on the line, such as by asking a question, seeking feedback, reporting a mistake, or proposing a new idea. One weighs each potential action against a particular interpersonal climate, as in, ‘If I do this here, will I be hurt, embarrassed or criticized?’” (An excellent read is Edmundson’s recent book, “Teaming:How Organizations Learn, Innovate, and Compete in the Knowledge Economy“.)

This is crucial to understand. An open-door policy may sound great from a leader’s perspective; they just have to sit back and wait for staff to come talk. But if individual staff members worry about being judged for “going to the boss’ office,” or believe that their boss will overreact—or, worse, do nothing—they may be reluctant to risk the effort.

Psychological safety may sound like a familiar concept, especially if you work with one of the many organizations that has invested in developing a strong culture of trust and respect. Psychological safety is related to trust, as both involve perceptions about risk and vulnerability. But the differences between the two are important, too: trust involves perceptions about another’s future actions towards you, and generally considers a longer-term timeframe across many interactions, whereas psychological safety is an internal calculation about how others will perceive a specific action in the relatively immediate future.

These differences are important, in two key respects. First, the focus of psychological safety’s effect is a near-term calculation. This means a person may choose a course of action with negative long-term consequences to avoid a short-term embarrassment or reprisal. Consider the all-too-common example of a CNA who observes an unsafe condition but fails to speak up because she is fearful of being labeled “a troublemaker.” The long-term potential for harm should outweigh the short-term risk of standing out—but often it doesn’t. Second, trust involves holding a belief about how another person will treat you in the future, whereas psychological safety involves an assumption about how your own actions will be perceived by others. Individuals with lower self-esteem and self-confidence may struggle to take risks even in environments where there is trust. In addition, the experience of the group tends to influence psychological safety much more than trust; if you witness a team member being criticized or embarrassed, you are much more likely to censor your own actions in defense.

A lack of psychological safety manifests itself in myriad ways: employees are less likely to speak up if they have concerns or reservations; co-workers may observe mistakes, but fail to call attention to them; managers stick to the status quo, rather than attempt a risky innovation or improvement effort; teams are less capable of achieving goals that require communication and interpersonal interaction.

So, how can a leader combat these tendencies within their organization? Here are 3 practices to promote a culture of psychological safety.

- Be vulnerable and take risks. A secure leader can model vulnerability for the team. Embrace weakness, admit mistakes openly, and demonstrate a willingness to take interpersonal risks. Pay particular attention to actions you are hesitant to take: are you worried about another person’s reaction? The company’s response? Your reputation? Confronting these fears head-on can help you identify places where other team members may be struggling, too.In addition to taking appropriate risks, explain the context around your actions openly. Leaders often unwittingly harm psychological safety by making decisions without describing context or alternatives; by doing so, they create an illusion that every action should be “certain,” which reduces risk-taking confidence in staff. Similarly, make sure that you don’t unwittingly punish staff for failures that come from prudent risk-taking. When handled appropriately, failures and mistakes should be celebrated for the learning opportunities they provide. Doing so helps to normalize imperfection and lowers the risks for others to make mistakes. (A commitment to Just Culture helps balance accountability with support.)

- Develop team competencies that contribute to psychological safety. As noted earlier, psychological safety is related to trust, but also has some important distinctions. Typical trust-building exercises focus on peer-to-peer or employee-to-supervisor relationships. By contrast, building psychological safety involves whole team discussion about the barriers and roadblocks to speaking and acting openly, and requires diligence in establishing and maintaining norms for acceptable and desired behavior (which should include making mistakes). In this regard, leaders must also be mindful about cliques that exist within departments or units, as these tend to normalize behavior in ways that limit risk-taking. Calling attention to appropriate instances where individuals took risks to speak up or take action helps to reinforce expectations and build support.Practice is also important: sometimes team members may come to an administrator to share something “confidentially” or “off the record”— rarely, however, do these concerns really involve a confidential matter; rather, they are a symptom of a lack of psychological safety in the team. Take the opportunity to prepare the individual, and then gather the team for the individual to raise the concern directly to the group. Show your support for this type of behavior, and use the instance in an upcoming staff meeting to highlight the risk individuals face, the benefits of speaking up (to both the team and to the residents being served), and the commitment the team can expect from leadership.

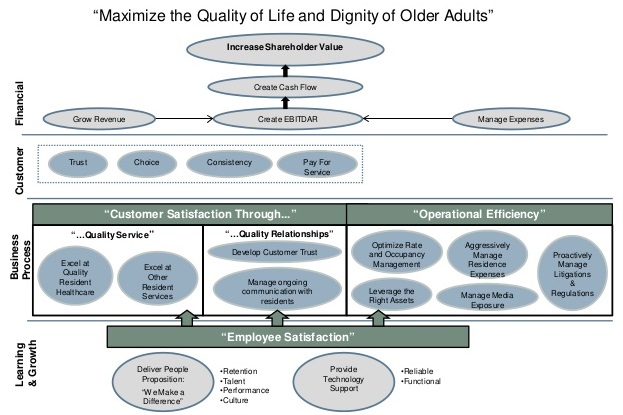

- Identify your True North. Purpose-directed organizations build safety by creating a shared vision of what is trying to be achieved. The Cleveland Clinic, for instance, identified “Patients First” as their true north, and constantly asks team members at all levels of the organization to focus on “what matters most.” By striving for a shared purpose, staff are freer to take risks because they can mediate discomfort or conflict with someone else by appealing to that overall goal instead of focusing on a specific action or behavior.

Increasing the psychology safety in an organization takes time, commitment and courage. But the benefits– improved patient safety, increased employee engagement, and strong, more resilient teams are well worth the struggle.