For many aging services providers, employee injuries are a costly reality of the workplace. In addition to workers compensation costs, however, employee injuries can cause scheduling challenges and lower worker morale. Lakeville Management, a small regional provider of assisted living and memory care communities, decided to tackle employee injuries as part of their commitment to deepening their respect towards employees.

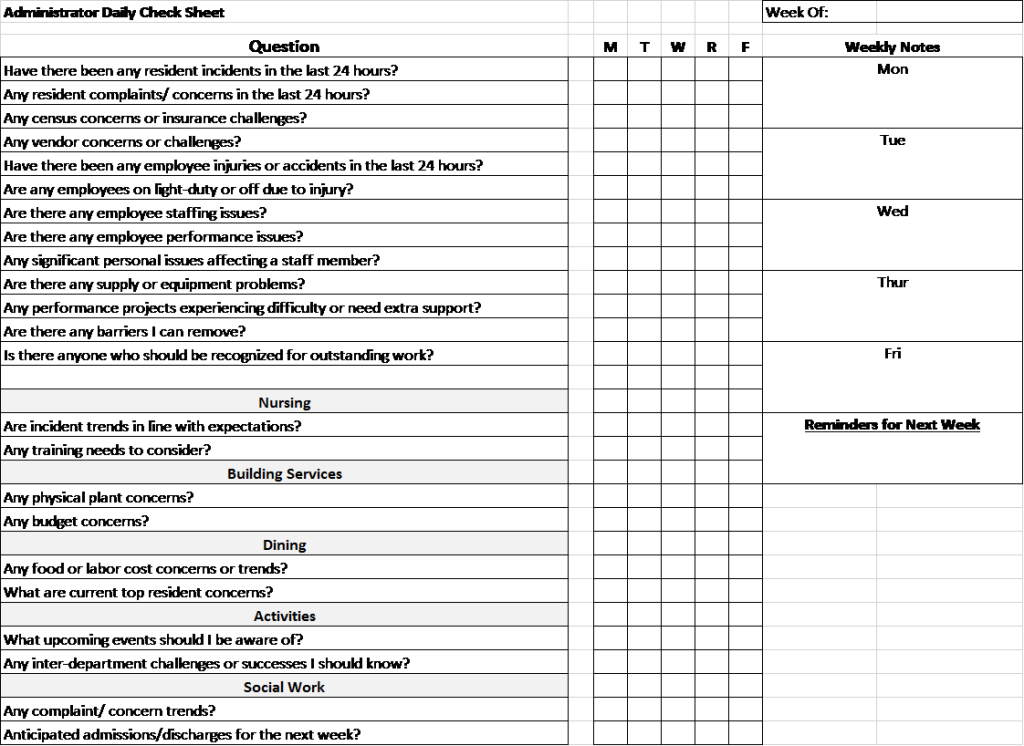

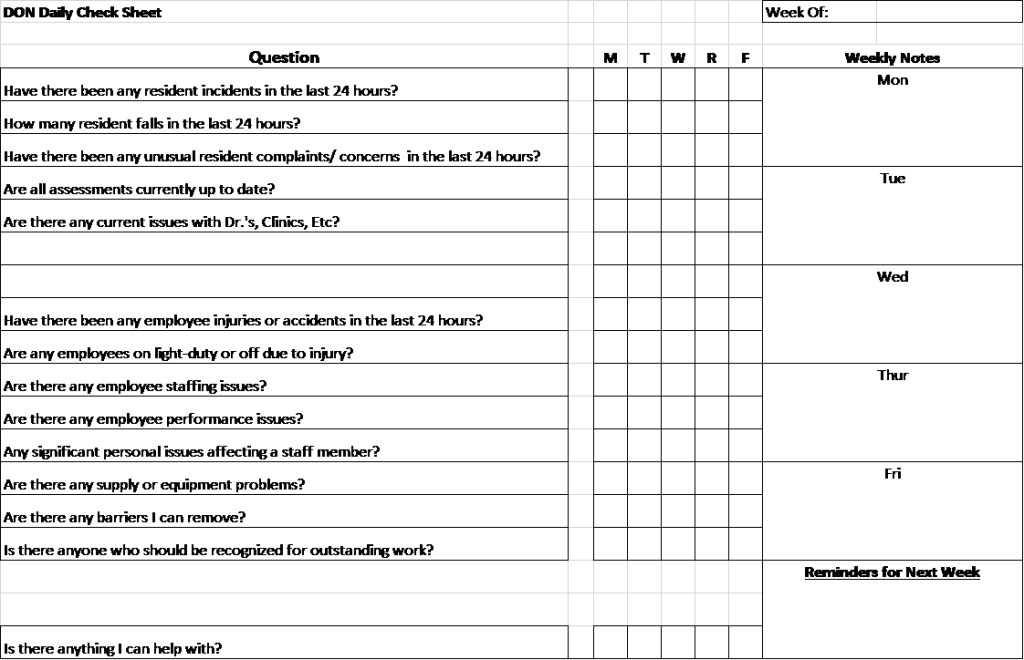

To begin, administrators held several small focus groups to solicit information about the current safety culture, the employee injury reporting process, and barriers to implementing changes. With this initial information, the leadership team was able to construct a company-wide survey and identify opportunities to improve their processes.

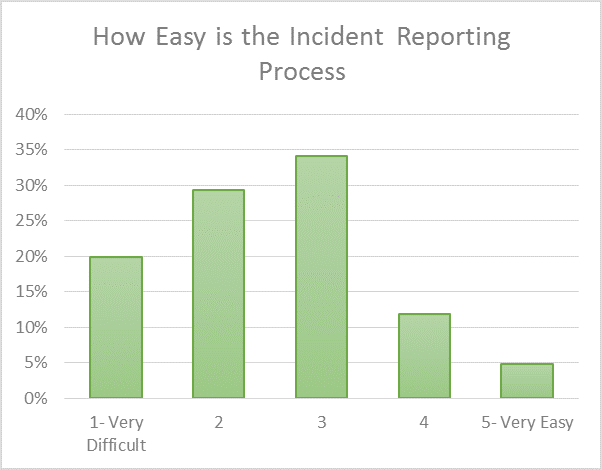

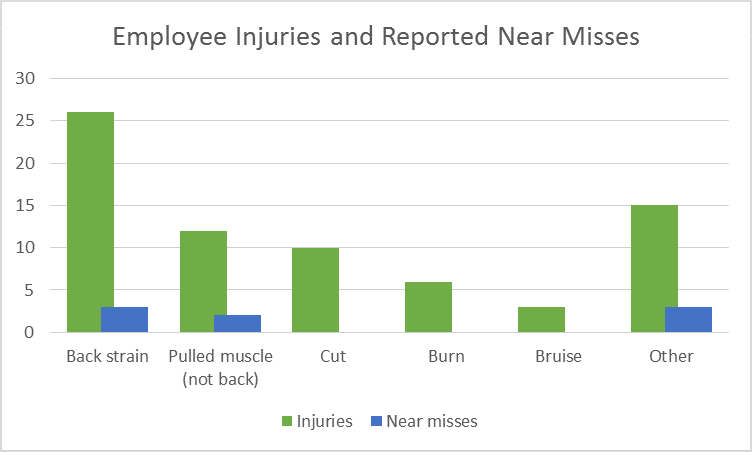

The company safety committee (composed of multi-disciplinary representatives from each member community) first examined their current incident reporting process, which was used to report both actual injuries and near misses. Staff reported that the process was somewhat difficult, and, as a result, very few employees bothered to submit near misses. In addition, by examining the type of injuries that occurred most frequently, the committee decided to focus education and interventions on muscle strains, which accounted for almost 60% of all employee injuries.

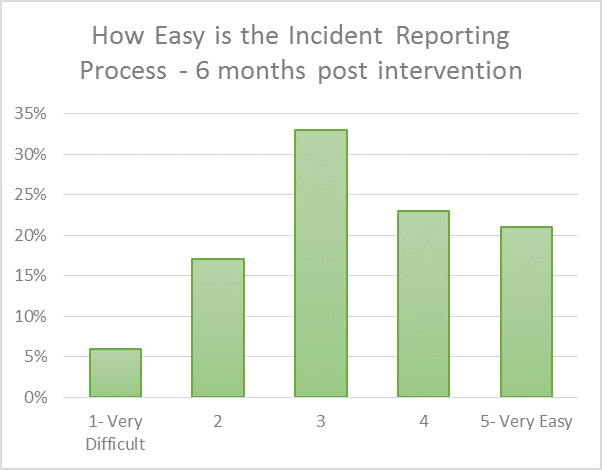

The committee began by mapping out the incident reporting process. By dialoguing with supervisors tasked with completing parts of the process, the committee identified pain points, unclear forms, and burdensome back-and-forths. Using this knowledge, the committee tested several process and form updates, refining methods after 30 day trials in a single community.

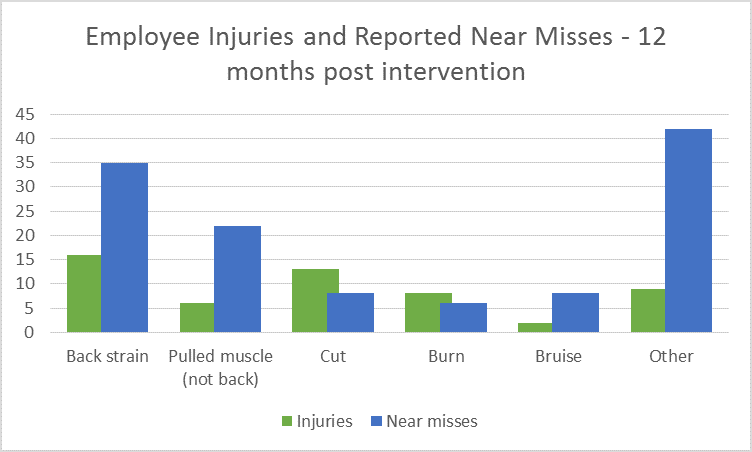

The organization also created a temporary contest to build awareness about the value of near-miss reporting, including incentives for reporting near-misses and a transparent process in each community where near misses and interventions were displayed on a visual control board located in the staff break room. Staff were able see the results of reporting dangers before they led to injuries and could weigh in on interventions to help ensure that proposed changes were realistic within work routines.

After six months of work and four rounds of the PDSA process, Lakeville reevaluated the incident reporting process ease and short-term results. Supervisors reported that the updated processes were much easier to follow, and the leadership team noted a strong increase in the number of near miss reports. After twelve months, the results were dramatic: almost $200,000 in avoided worker compensation costs, 63% fewer lost days, and 15% fewer modified work days. In addition, managers at Lakeville became accustomed to including a review of staff injuries and near misses as part of their daily work, increasing accountability and awareness for the importance of worker safety to the organization.